- Keep Cool

- Posts

- The world-ending fire

The world-ending fire

And why it’s not exclusively a climate change ‘story’

The fires still raging in Los Angeles and the surrounding area are cataclysmic, catastrophic, devastating. It’s one of those situations where words—ever an imperfect abstraction of human experience—fail. While I called LA home for the better part of a decade, I can’t say it’s been particularly devastating for me, save for the toll on my mental capacity as I extend care and prayers for my friends out there (all of whom are safe) and the drain that any devastation anywhere in the world has on my soul.

A satellite view of Altadena ablaze on the morning of January 8th (Source: Maxar Technologies)

The fires are also a stark wake-up call. As I wrote on Sunday:

For one of its first acts, 2025 has already reminded us that resilience & adaptation will be as critical as greenhouse gas emission and other environmental externality mitigation, if not more so, for the foreseeable future.

While words are oft insufficient, sometimes numbers help paint a slightly better picture.

The fires (of which there have been many separate ones) have been blazing for more than a week, claiming dozens of lives and burning an area many times larger than the New York City borough I moved to from LA. As the fires continue, the estimates of financial losses and damages—such as those driven by property and infrastructure destruction—are mounting in Mount Everestian fashion. At first, initial damage estimates were coming in at $20 billion. Then $50 billion. Now, they’re up to $250-275 billion.

They may keep climbing higher. Even if $250 billion is simply close to being in the right ballpark, it’s a mind-boggling number, one that comes disconcerting close to matching the total damages caused by all the natural disasters worldwide over the entirety of 2024.

The damages caused by the LA fires may alone eventually match or even surpass the total damages caused by all natural disasters worldwide over the entirety of 2024.

Munich Re, a major global reinsurance company, recently released its annual report for 2024 on catastrophic losses related to weather events for 2024, with a tally that came out to about $320 billion. So, yeah, these LA fires may well surpass that on their own.

But even these staggering numbers and statistics fall short of hitting home the ‘true’ cost of even the loss of one human’s life. They are primarily focused on categories like physical property—homes, buildings, schools, and commercial real estate—and other infrastructure. They don’t take into account, say, residual and often-long lasting externalities on human health, such as those driven by the air quality that fires worsen, let alone the value of lives, human or other, lost. The ‘true’ cost of all that is, frankly, incalculable. Suffice it to say, the tragic fires will likely be the costliest and most consequential natural disasters in U.S. history, if not in global history.

In the same way that it will take time before we know just how damaging the fires were, it will take time to know exactly what mix of conditions and catalysts caused them. Of course, many are quick to yell, “Climate change!” But there’s more to this story than that. Which is where we will now dig in.

Proximate causes and inappropriate conclusions

For more than a week, multiple fires have devastated Los Angeles and the surrounding region. Each was likely started, fueled, and exacerbated by a mix of catalysts and conditions. Most were likely made worse by fiercely strong Santa Ana winds and the presence of substantial “fuel” in the form of new growth and vegetation in forests and landscapes around LA after a few wet years. These may be commonalities shared by multiple fires.

In other ways, the proximate causes and accelerants of each fire will differ. Some may have been sparked by power line failures (another source for more reading on potential power line failures as a cause of the Hurst fire near San Fernando lives here). Others might have been sparked by BBQs. Or arsonists. Or failures in any electrical infrastructure. The Grenfell Tower tragedy in the U.K. some years ago involved a fire sparked by an electrical fault in a refrigerator on the fourth floor of the building. The building’s cladding, which had been added for enhanced thermal performance, also contributed to rapid fire propagation. The fire claimed the lives of 72 people and injured many more, another reminder of the subtle but omnipresent dangers inherent to basically all electrical infrastructure, regardless of whether it is new and innovative or not.

Firefighting efforts in LA amidst the ongoing fires were also retarded by more ‘basic’ failures, such as fire hydrants that were insufficiently equipped and designed to handle the demand for firefighting efforts (more analysis on why is pending there, too)

A fire hydrant burns in the Eaton fire on January 8th. JOSH EDELSON / AFP (Via Business Insider)

Other factors that perhaps surprisingly cropped up as challenges to firefighting efforts extend to things like drones. Firefighting helicopters are one of the most dangerous places where you can find yourself working. Add high winds to the mix, and you’re in even more danger. Then, add drones flying around to capture photos—which you might collide with—and you’re in an entirely new dimension of danger.

As reported by Jeva Lange for Heatmap:

Last week, a drone punched a hole in the wing of a Québécois ‘Super Scooper’ plane that had traveled down from Canada to fight the fires, grounding Palisades firefighting operations for an agonizing half-hour. Thirty minutes might not seem like much, but it is precious time lost when the Santa Ana winds have already curtailed aerial operations.

Woof.

Surprise. This is not predominantly a climate change story

Make no mistake: I firmly believe climate change made these fires more likely and may have made them worse than they might otherwise have been. That said, whether atmospheric carbon dioxide levels were still at 320 parts per million (ppm), as they were around 1965, or 420 ppm, which they’re beyond as of 2024 and 2025, these fires were always possible, if not likely to happen, climate change or not. Just like another giant earthquake will rock California someday (*gulps*).

Via Richard A. Betts, Chris D. Jones, Ralph Keeling, Jeff R. Knight, James O. Pope, Caroline Sandford

Dave Jones, California’s former insurance commissioner, put it plainly:

…[fires like these happening] was never a question of if, it was a question of when…

Of course, there is a climate change story here. For one, single-event attribution to climate change is incredibly complicated and a relatively nascent area of science and modeling. It’s not something I intuitively trust when I read headlines like “Climate change made X event Y% more likely. That ‘simply’ reeks of over’simpli’fication.

I do appreciate and trust researchers and their efforts, such as those investigating what climate researchers refer to as "hydroclimate whiplash," where you move from wet to dry conditions or other abrupt environmental changes quickly, made these fires more likely. As noted by Daniel Swain, a climate scientist at my alma mater, UCLA:

[Climate change] is increasing the overlap between extremely dry vegetation conditions later in the season and the occurrence of these wind events.

That said, the same researchers focused on hydroclimate whiplash also said:

We believe that the fires would still have been extreme without the climate change components but would have been somewhat smaller and less intense.

Again, I add all this not to discredit the work but to set up where I want to go next.

The IPCC, one of the most respected bodies in climate science and research, is also a touch cautious in terms of the extent to which it ties observed climate change to date to worsening wildfires in North America (my emphasis on things like ‘medium confidence’ added in bold):

Anthropogenic climate change has led to warmer and drier conditions (i.e., fire weather) that favour wildland fires in North America (high confidence)... In response, increased burned area in recent decades in western North America has been facilitated by anthropogenic climate change (medium confidence)...

None of this language parallels the way many climate communicators engage with disasters like the Los Angeles wildfires. Many are, unfortunately, quick to take something like these LA wildfires and make it a climate change story, through and through, full stop. This has been a disastrous climate communication strategy for decades now. For one, you can look at whether pinning every possible disaster on climate change has made an impact. My bird’s eye view, with greenhouse gas emissions globally across most, if not all, major warming drivers near all-time highs, says no.

Secondly, the ‘climate change is everything’ communication strategy is far too prone to simple dismissal from naysayers every time there’s a cold snap, an unseasonably snowy winter, or when people make predictions about what horrors climate change will reap that (thankfully) don’t always come to fruition. Rather famously, Al Gore’s Inconvenient Truth predicted that climate change was the cause of and would continue to cause more frequent and more intense hurricanes. An image of a hurricane constitutes the entirety of the movie's cover.

Inconveniently for Gore, but thankfully for all, neither hurricane frequency nor storm intensity has necessarily increased all that substantially in recent decades, at least not in a reliably discernible and scientific fashion. Damages have increased, and things like inland flooding from hurricanes and rapid intensification of hurricanes have, too (I wrote about this here), but the increased damages likely stem primarily from the rate at which infrastructure is built in high-risk areas (more on that shortly).

As far as the IPCC will go on hurricane and tropical cyclone frequency and intensity is to outline observed changes as follows (emphasis again my own):

It is likely that the global proportion of Category 3–5 tropical cyclone (TC) instances has increased over the past four decades…TC translation speed has likely slowed over the conterminous USA since 1900. Evidence of similar trends in other regions is not robust. The global frequency of TC rapid intensification events has likely increased over the past four decades. None of these changes can be explained by natural variability alone (medium confidence).

Other research suggests the destructiveness of tropical cyclones has actually been falling:

The report source on “Decreasing trend in destructive potential of tropical cyclones in the South Indian Ocean since the mid-1990s” can be found here.

Suffice it to say, it’s hard to say! If I know one thing, it’s that not everything bad that happens under the sun is ‘about’ climate change. In the same way that fires have many causes and accelerants, natural disasters and damages related to them do, too. Likely, the most significant driver of increased damages due to natural disasters in recent decades has been the rate at which people moved to and built significantly more infrastructure in disaster-prone areas. As articulated by Swiss RE, a massive reinsurance company:

...growth in natural catastrophe-related property losses has been mostly driven by rising exposures due to economic growth, accumulation of asset values..., & rising populations, often in regions susceptible to severe weather events…

The tl;dr is that attribution of what damages are “caused” or at least exacerbated by climate change is perniciously tricky, as building more infrastructure in disaster-prone areas itself is a more proximate cause of escalating damages.

Overemphasizing climate change’s responsibility for natural disasters also, and perhaps most importantly, detracts from the story I’m most interested in. Which is how unsustainable so many of our societal systems are, independent of any discussion of climate change.

It’s (almost) all unsustainable

Framing all this as principally a ‘climate change’ story does a disservice to the realization we should be coming home to, namely that there’s an inherent unsustainability to almost everything about much of modern society. It’s unsustainable that fire hydrants aren’t equipped to sustainably provide sufficient water pressure to fight intense fires in Los Angeles. It’s unsustainable that the world’s waterways are filling with trash and PFAS and microplastics at alarming rates. It’s unsustainable that prisoners get paid a maximum of $10.24 per day to do heroic firefighting. They should get paid $20 an hour. Or $200 an hour, probably.

It’s unsustainable that so many Americans are in prison in the first place—including many who may be incarcerated for ‘crimes’ like marijuana-related charges—even as marijuana is now mostly as ubiquitous and socially accepted as alcohol. Governments would have more money to fund adaptive efforts and infrastructure upgrades if the U.S. didn’t lead the world in incarceration rates, which costs a ton, strains the U.S. workforce, and ruins lives.

It’s unsustainable that an almost 100-year-old PG&E power line may have sparked the 2018 Camp Fire, which killed more people than the LA fires have so far. It’s unsustainable that most wastewater treatment infrastructure in the U.S. is, on average, close to 50 years old. It’s unsustainable that there are more than or close to 1 billion cattle, goats, and sheep on Earth, as the methane they belch out drives roughly 10% of observed global warming in and of itself.

Insurance, at least as traditionally structured, is wholly unsustainable in many parts of the world now. This topic alone could fill dozens of newsletters (some reading here, here, here, and here).

Perhaps it’s unsustainable that many millions of people live in the water-starved Southwestern U.S. to begin with, even as more and more people move there, not just to LA, but to Arizona and elsewhere. Sure, technological innovation has staved off the most Malthusian predictions many times over the course of history. ~80% of wheat grown globally today has traces of Norman Borlaug’s rust resistance genes in it, an innovation for which Borlaug won the Nobel Prize in 1970. Similarly, ~50% of the nitrogen in your body right now can be traced back to the use of the Haber-Basch process, used to make ammonia, a fertilizer to make crops more productive. That process was invented about a century ago. Without it, there’s no way the world could support a population of 8 billion people (and growing). Fritz Haber, one of its inventors, also won a Nobel.

The world has never run out of a core commodity. But that doesn’t mean we never will!

As humans, we have, time and time again, outstripped iterative natural limits, whether by flying planes and sending rockets into space or doing all kinds of other highly technical engineering, like creating unimaginably pristinely clean manufacturing environments, insanely powerful semiconductors, or whatever else comes to mind for you. More simply, even the fact that we routinely provide electricity to the majority of people on Earth is itself a miraculous feat.

Maybe we won’t be able to break through and survive forever, though. So, while I disagree with most of what he gets up to these days, I can appreciate why Musk is so obsessed with colonizing Mars or why others are so obsessed with recreating human-like consciousness in machines. Even if I don’t hear the siren songs of those things myself.

Lastly, in the vein of calling out what’s unsustainable, it’s unsustainable that I’m sitting here, trying to write comprehensibly about sustainability while I haven’t slept in 28 hours. Which brings me to my next point → The necessary shift starts with you and me.

What’s to be done?

One of my favorite quotes from Wendell Berry’s book, The World-Ending Fire (topical title), which he wrote in 1970, is:

...We must do more for ourselves and each other. It is either that or continue merely to think and talk about changes that we are inviting catastrophe to make. The great obstacle is simply this: the conviction that we cannot change because we are dependent on what is wrong. But that is the addict’s excuse, and we know that it will not do.

Hear, hear! Berry also wrote presciently about the loss of topsoil, which is critical to agriculture and the Earth’s climate systems in general. Topsoil is the layer of soil with the highest concentration of organic matter and microorganisms, home to most of Earth's biological soil activity. Topsoil loss, too, is still ongoing, if not worsening; add that as another line item on our laundry list of unsustainable systems, or at least symptoms of our collective “unsustainability” disease.

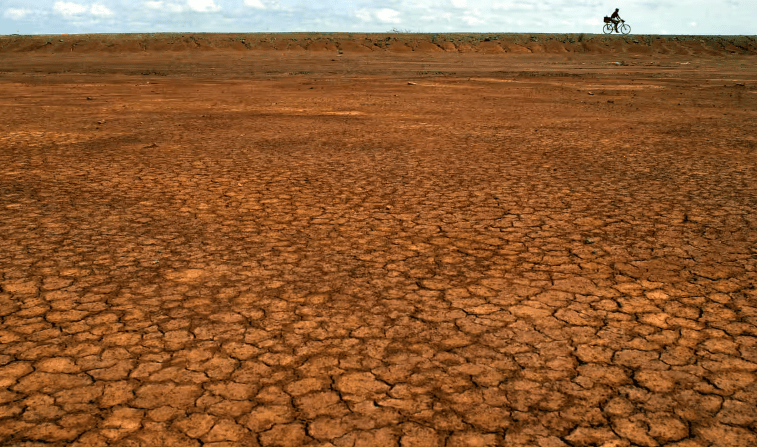

The Sarigua desert, west of Panama City, Panama, exhibits significant topsoil erosion after overgrazing by livestock. Photograph: Tomas Munita/AP. Via The Guardian.

Going back to the Berry quote, while inspiring, it’s, as usual, easier said than done.

So. What do we do?

I’m a bit short on sage suggestions. There is so much to be done, given how unsustainable so many of our societally load-bearing systems already are. There’s rebuilding more fire-resistant homes. There’s an urgent prerogative to develop new firefighting technologies (perhaps starting with better fire hydrants!). There’s a need for more efficient and responsible resource allocation across all levels of government. There’s probably a need to overhaul insurance comprehensively while iterating on novel, adaptive models for specific natural disaster risks. There’s making the financial capital stack, including in venture capital, more responsive to niche needs, like better fire prediction and mitigation technologies. There’s all that and, of course, much, much more.

But for you and I? Likely, some of the best work we can do is continuously resource ourselves, our loved ones, and our local communities. From there, we’re in a more sustainable position to bite off a handful of other discrete areas of targeted investigation and impact that we’re genuinely curious about (again, that makes things more sustainable) that could help make some facet, some blade of grass in our own little slice of our own little proverbial garden (a la the famous Voltaire quote), a touch more sustainable. There’s no shortage of places to start. You can start practically anywhere.

As Berry points out in the above quote, it’s easy to point fingers at the “big bad” utilities and/or insurers, or the failures of government officials, or arsonists, or the comprehensive climate change bogeyman. It’s harder to recognize that, with respect to getting anything done, it does ultimately still require my and your participation. So start by resourcing yourself, which is something I’m still quite bad at. Then, maybe start with a little bit of work towards a more sustainable system. Then maybe talk to your family about it. Then maybe engage your friends. Then, maybe approach the ever-broadening, concentric circles of communities you can influence, at least to the extent you have the capacity to do so while adequately resourcing yourself.

The net-net

As Billy Joel sings in his song, We didn’t start the fire:

We didn't start the fire

It was always burning, since the world's been turning

We didn't start the fire

No, we didn't light it, but we tried to fight it

My angle in all this is to push back on another longstanding trope of climate communications and collective climate activism and organization; the other we discussed was the act of making everything out to be about climate change all the time. Entering 2025, as we have with these cataclysmic fires and a much less environmentally focused federal administration waiting in the wings, individual action matters as much, if not more than ever. Yes, emphasizing the importance of individual action was a strategic marketing campaign orchestrated by oil companies to shirk their own role in spiking greenhouse gas emissions, atmospheric concentrations thereof, and the warming all of that drives. No, that doesn’t absolve any of us or give us license to abnegate the impact we are capable of.

No, I don’t think individual action alone can comprehensively reshape all the systems we’ve discussed to make them more sustainable. But what definitely counts, at minimum (and potentially maximum!), is our attention to how unsustainable most of modern society is. Attention is, at this point, and as I and others have written about, becoming both one of the most valuable commodities in an increasingly digital economy and one of the most precious, personal, divine possessions we all have and can cultivate more of.

As writes Daisy Alioto (brilliantly as always):

There are periods of your life when you have nothing to offer but your attention and that is genuinely humbling... To my mind, even the briefest gift of human attention is worth a thousand conversations without refusal.

The fires are a catastrophic call to attention. To offer attention to those in Los Angeles, or wherever else in the world, incomprehensible horrors are unfurling—as they always are somewhere. To pay and draw attention to climate change in a conscientious rather than dogmatic and proselytizing fashion. To call attention to the countless other systemic, unsustainable ills.

Further, let us, for once (finally), not stop offering attention when the fires do subside. Because they will. And then they, or the next thing, will come.

We will likely sail past 2°C of global warming in a few decades or generations. Some, if not many of us, will be around to live through whatever that world is like. The questions then, as always, will remain:

“What do we want to do with the time we have left?”

And:

“What do we want to train our attention, which renews daily, like a rising sun, on?”

Take good care,

– Nick

Reply