- Keep Cool

- Posts

- Biodiversity: Why you should care

Biodiversity: Why you should care

I recently read the seminal “Thinking in Systems” by Donella Meadows. In it, I found a paragraph that clarified in thirty seconds what three years of covering climate tech hadn’t yet around one key question: Why does biodiversity matter?

I’ve always been a lover of biodiversity. So much so that when we did research reports on endangered species in the fourth grade, I willingly did the assignment twice (sorry to any of you who were in class with me who had to sit through an extra presentation).

But scientists and policymakers don’t just care about biodiversity because it’s nice to have pretty animals and plants around as a backdrop for human life on Earth. Why? Here’s Meadows:

When you understand the power of system self-organization, you begin to understand why biologists worship biodiversity even more than economists worship technology. The wildly varied stock of DNA, evolved & accumulated over billions of years, is the source of evolutionary potential, just as science libraries and labs and universities where scientists are trained are the source of technological potential. Allowing species to go extinct is a systems crime, just as randomly eliminating all copies of particular science journals or particular kinds of scientists would be.

When you see announcements, like one earlier this year surrounding a new High Seas treaty – reached after twenty years – that aims to protect 30% of all oceans and seas by 2030, it’s not just a feel-good story. The bigger goal is to preserve as diverse a stock of DNA as possible. Because there’s simply no calculating the value of that.

We owe our own existence to the existence of a diverse bank of DNA in the past that helped foster our evolution. Lose biodiversity, and you’re losing a tremendous amount of evolutionary potential.

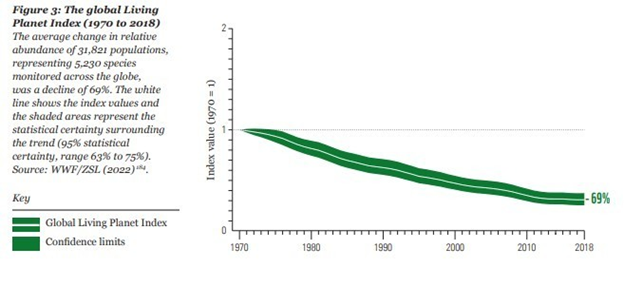

The race to expand biodiversity protections is motivated in part by how much we’ve lost in a short time. By some UN estimates, a quarter of all animals and plants could face extinction in our lifetimes. And if you measure the ‘abundance’ of different keystone species, declines over the past fifty years are even starker.

Again, when I used to hear stats like these, it made me sad. But I didn’t appreciate them as threats to the evolution of life on Earth.

These trends also explain why some people are soup-in-arms about the Biden Admin’s recent approval of new oil leases in Alaska. Not only does this go against Biden’s campaign promises. Nor is it just about the CO2 emissions it will produce. The development will threaten an otherwise pristine, intact ecosystem.

At this point, I can imagine a few of you saying, “Gee, Nick. Way to turn up the optimism dial!”

I hear you. Let’s find something nicer to talk about. Namely, great teams working on the complex solutions ecosystems deserve and need.

Tell me some good news

There is no single techno-economic fix to the challenges surrounding climate change, biodiversity loss, or, as Kristin McDonald wrote in this great deep dive on all things biodiversity and corresponding climate challenges, all other “cascading, interlocked environmental crises.” The systems in place that drive these crises are complex, as are the ecological systems they threaten.

And complex problems require complex solutions.

At the highest level, however, a lot of progress will depend on reevaluating land use. That’s where enterprising startups are working to build new models for how we reimagine land stewardship.

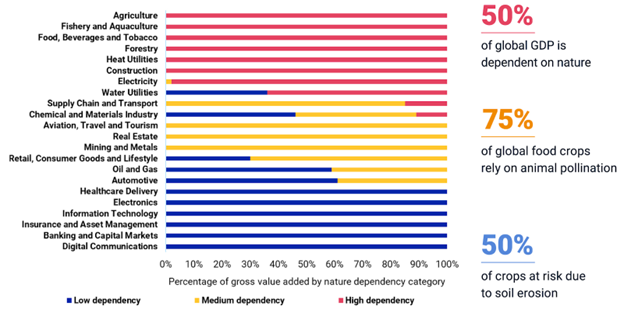

Before we meet them, if you frame this topic purely economically, you can still appreciate its importance. You don’t have to care about preserving diverse stocks of DNA in flora, fauna, and fungi to care about preserving rich, productive land. Many of the world’s biggest industries would and will be brought to their knees if ecosystems deteriorate beyond repair.

The problem is that when we reduce the value of land to a purely economic perspective (what we normally do), we don't do a good job protecting it. At most, people analyze the value of commodities produced on land, or perhaps slightly more ambitiously, also evaluate its carbon sequestration potential.

These narrow, short-term, output-focused perspectives accelerate or do little to thwart ecosystem degradation, whether from overgrazing, deforestation, monocropping, or flawed carbon development.

In a conversation with Colin Averill, the Founder of Funga, he described the challenge as follows:

The history of agriculture and biotech has been hugely reductionist... Every time we try and reduce it, we run into unforeseen consequences.

What do better models look like? To start, they have to at least approach the complexity of ecosystems themselves. Measuring one or two variables isn't enough to properly 'value' any ecosystem or the benefit of more regenerative land stewardship.

Fostering fungi in forests

One big motivator for Colin in founding Funga is global microbial biodiversity decline. He has done significant academic work studying and reporting on this decline. As Colin wrote to me as we kicked drafts of this newsletter around:

The first life on Earth was microbial. It's really important we work to guard this invisible foundation of biodiversity.

Fungi are one foundational aspect of forests. Funga's mission is to prove that if you foster more fungal biodiversity (and understand it better), you'll reap significant rewards, both when measured by traditional metrics (timber output) and by others, like soil quality or biodiversity.

An essential piece of that mission is proving to investors and potential stakeholders that more holistic ecosystem restoration work can translate into higher land values, cash from carbon and perhaps biodiversity credits, and demand from sustainability-minded buyers of things like timber.

What does Funga do? For one, they're conducting significant fungal DNA sequencing to better understand questions like how fast trees grow, their likelihood to survive drought, their carbon capture rates, and more across the 500+ forests (so far).

They pair with more macro forest inventory data and want to build the most extensive dataset of forest ecosystems ever assembled. Ideally, all this data will tell a story that corroborates their thesis around the value of fostering fungal biodiversity. Incidentally, this effort ties well into something I’ve talked to a lot of CEOs about of late, whether they’re focused on batteries or biodiversity. AI is cool. Unlocking new data to feed into AI and ML applications is even cooler.

Fungal biodiversity poking its head out in a Karri forest (Shutterstock)

Lest I forget, Funga also reintroduces fungi into forests. During the past planting season (November to March roughly), they worked on 120 acres of forest fungal restoration projects. Next planting season they’re targeting 2,500 acres. They estimate these footprints alone will capture tens of thousands of tonnes of CO2, and they see a path to gigatonne scale.

To do all this work, Funga also needs runway. Institutional recognition that there’s opportunity here is coalescing; Funga recently raised a $4M seed round.

But a seed fundraise is one thing. Revenue is another. Currently, carbon credits are the dominant mechanism available to firms like Funga to monetize their work. Still, as we've tracked, carbon sequestration is only one of many impacts the work could have.

As we often bump up against, there's a chicken vs. egg problem here. The big challenge (and opportunity) is to build partnerships with diverse stakeholders who are believe in this work, even before the financial systems are in place to value and monetize all its benefits. That (ideally) includes landowners, local communities, and multinational corporations, say, IKEA, that want to shore up the sustainability of their supply chains (IKEA uses ~1% of the world's timber).

The future of the farm

Another firm integral to my interest in this topic is Farm. I've sat down with Tim Luckow, the CEO of Farm, a few times now, and he's turned me on to some big ideas surrounding farmland. America's farmland is one of its many riches. Still, much of it has degraded over time due to overgrazing, monocultures, synthetic fertilizers, pesticides, and more (all of which also threaten biodiversity).

This isn't new; many of the factors that created the Dust Bowl ~100 years ago threaten farmland in this century. And the change vector here is similar to Funga's approach. Farmland assets have been viewed one-dimensionally for a long time. It's time to shift towards a more multi-dimensional view.

On this front, the idea of 'natural capital' is gaining traction; institutional real estate investors are starting to use the term. The concept of natural capital asks us to consider what the value of land is when viewed from both:

A development lens ("Would this be valuable to an energy developer, whether to deploy solar or wind or for the rights of way to build a transmission line?")

And an even more holistic perspective, including questions like "Is it in a watershed?" "What biodiversity could it foster?" and "What's the soil health look like, and what could it look like?"

As we explored with Funga, ideally, richer datasets will help popularize this thinking as the whole host of benefits that ecosystem restoration unlocks becomes more visible.

The challenge Farm is tackling is the same as for Funga: how do you slot this thinking into the existing economic frameworks? Here's Tim on the opportunity:

If you start with a farmland investment perspective, it's a matter of leases and partnerships. Every agricultural operation leases land, whether itself or from an entity. And the same is true for energy developers: There's more project development interest than available acres. So one challenge is figuring out the right mix of productivity and conservation and the right mix of stakeholders.

That's Farm's work: Crafting the right partnerships between diverse stakeholders to implement better practices, technologies, and to bring a longer-term, more holistic perspective to land development.

One example? Wild Idea Buffalo, a project in South Dakota that transitioned their land from cattle ranching to bison ranching. Bison ranching has significant benefits compared to cattle ranching; bison are native to the Great Plains and are thus, great for the land.

Farm is working with the Wild Idea Buffalo team to find more land for them to grow and for their bison to spread their ecosystem restoration benefits.

Happy bison, happier land. (Photo via Wild Idea Buffalo)

To make the project more multi-dimensional, the teams are exploring co-locating bison farms with wind turbines. While investors aren't entirely onboard yet – as bison grazing projects aren't their usual underwriting fare – proving the model can be as if not more lucrative, if not more so, than conventional agriculture is Farm's goal.

The net-net

When I recently caught up with Diego Saez Gil, the CEO of Pachama, he echoed a similar sentiment regarding what can drive real systems change in land use. He noted technology is a significant driver, but the partnerships firms like his, Farm and Funga build underpin it all:

Permanence is enabled by technology, but is based on a network of human commitments.

In case the length of this newsletter wasn't evidence enough, this is one of the topics that most excites me these days. Natural systems are the only solutions that approach the complexity of the ecosystems that need regenerating. Marrying technology, data, and more creative, comprehensive partnerships to foster them is some of the most important work for folks to focus on right now.

Reply